What is in a name? Biologists use a precise system for naming species, but why and to what end? Here, PhD student James D. Burgon (@JamesBurgon), an evolutionary biologist and trained taxonomist, comes out from behind his Naturally Speaking editorial role to give us an insight into binomial nomenclature.

A brief foray into scientific nomenclature

Nestled behind multiple doors, and up hidden staircases, lies the rooftop labs of our Institute’s Graham Kerr building. Here you will find a rag-tag group of researchers toiling with some burning questions in evolutionary biology. Like many scientists we are also caffeine addicts, and use coffee breaks to discuss important topics – today it was funny names. There is a lot of information in a name. Hans Recknagel – masculine and German. Aileen Adam – Scottish and feminine. North West? Well, let’s withhold opinion on this celebrity child’s name, but it is misleading in having little to do with navigational bearings. Yes, there is a lot of information in a name, and this did not escape the attention of taxonomists.

Taxonomy fascinates me. This much-maligned branch of biology, the importance of which is often underestimated, sets my heart aflutter. The eminent evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky once said, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”. This led to another saying, heard in hushed tones behind the closed doors of museums – nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of taxonomy.

The Origin of Scientific Names

Taxonomy is the combination of classification and nomenclature; though the two are kept strictly separate. It is the act of finding species through shared characteristics, describing, and naming them. It is the means by which biologists get the units they use; it is the foundation on which the rest of biology builds. Saying, “Spotted flycatchers (Muscicapa striata) were seen feeding upon crane flies (Tipula paludosa)”, makes more sense than “bigger flying things ate smaller different looking flying things”.

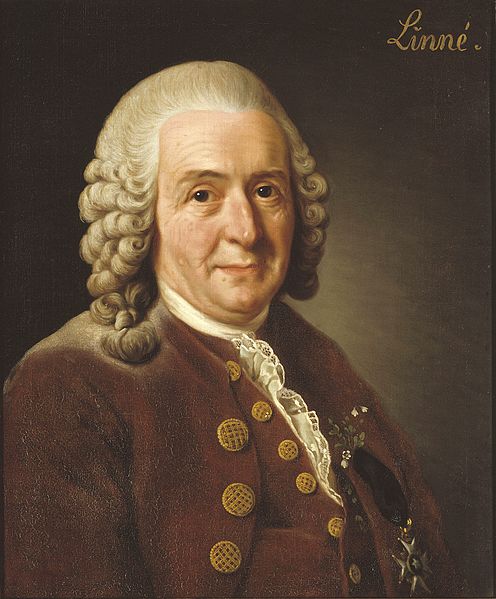

Linnaeus was an avid collector of plant and animal specimens from around the world, amassing extensive collections himself in Northern Sweden in the 1740s. So when he came up with a new system of classifying plants he wanted something simpler. As a result, in his 1753 publication Species Plantarum he did something that would change the face of biology, he invented binomial nomenclature. He used a ‘trivial name’, one composed of two simple Latin words that would be unique to each species. It rapidly developed as Linneaus unashamedly self-promoted and prolifically named species; his Species Plantarum was swiftly followed by his Systema Naturae, the tenth edition, published in 1758, being the start of modern day animal nomenclature. These trivial names caught on, and soon supplanted “correct names”; replacing the laborious Solanum caule inermi herbaceo, foliis pinnatis incisis with the succinct Solanum lycopersicum (the tomato’s current scientific name).

Why was this so important? Many people will point out that animals already have names, common names, but there is a problem with these. My current research focuses on the European fire salamander, but in Germany it is called the Feuersalamander, in Turkey the Lekeli Semender, and in Greece the Σαλαμάνδρα – in fact, it has a different name in every European country. If we used so many names it would be easy to miss data, and so restrict scientific research. Some species even share names: both North America and Europe have robins, but they are very different species.

A binomial name brings order to chaos, and stability to the literature, by designating a single name that is used by all researchers. In the case of the fire salamander, it’s Salamandra salamandra. The first word is the generic name, shared by all members of a genus (a group of closely related species), and the second is the specific name. Each unique combination is held by a single species and is anchored to a type specimen, a physical reference that can be referred back to – in the case of humans (Homo sapiens) these are the bodily remains of Linnaeus himself! (Though they respectfully left him in his grave, we know what humans are). The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) and the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), regulate the whole process. While they hold no real authority, they receive great respect due to the value of the shared system.

The Importance of Names: The Personal Case Study

Taxonomy and nomenclature have played a key role in my research. My undergraduate project was on the Amblyomma tick infections of cane toads in Trinidad, where I spent hours bent over a microscope using Koch’s (somewhat inadequate) 1844 treatise trying to identify the species of tick I was looking at. The confusion over the cane toad’s current scientific name (it is Rhinella marina, I checked, extensively) also got me hooked on nomenclature and classification. I ended up studying for a master’s in Taxonomy and Biodiversity at the Natural History Museum in London, where I worked with two brilliant taxonomists: former Executive Secretary of the ICZN Dr Ellinor Michel, and paleontological mollusc curator Dr Jon Todd. This started an ongoing collaboration on the systematics of the freshwater snail genus Paramelania, endemic to Lake Tanganyika in Africa. Our work expanded the genus from the two currently accepted species to 21 (16 new to science!). As we prepare to publish our findings, our minds turn to names. Perhaps, like Linnaeus, we will name some after people we respect, which has become a common trend in science – luckily his habit of naming “unpleasant” species after people he disliked did not catch on (much).

Many people claim that it is time to call quits on binomial nomenclature, arguing that it is antiquated and inadequate. The alternative? One suggestion is DNA barcoding, which uses unique genetic markers as an identity tag, though there is a lack of particularly suitable markers. Another alternative in use are numeric codes, like the European Union for Bird Ringing (EURING) codes. These are unique five digit codes assigned to individual bird species and subspecies, e.g. southern grey shrike (Lanius meridionalis) is 15203. But the beauty of binomial names is not only in their simplicity, but in their poetry and memorability – we are beings of words, and names hold a certain power. While barcodes and numbers may come to play an important role, Linnaeus’s ‘trivial names’ have reigned for over 250 years, and as I sit planning what to call my first new species of Tanganyikan snail, I can’t see that changing soon.

One thought on “The importance of names”