A resident MRes student’s historical view of the Scottish Centre for Ecology and the Natural Environment (SCENE)

Scotland’s Loch Lomond, a vast and brooding expanse of water stretching 36.4 kilometers, is more than just its superlatives. Beyond being the largest lake in Great Britain by surface area, its true enormity lies in the history it has mirrored and the legends it has cradled. Long before written records, Picts and Gaels roamed its shores, carving their identities into the land through battle and belief. Viking longships later cut through its waters, plundering settlements and leaving their own mark on the loch’s story. It has seen the thunder of clashing steel in the Battle of Glen Fruin, where the MacGregors’ defiance led to their exile. It has carried the whispers of warring clans and harboured outlaws like Rob Roy MacGregor, weaving their exploits into the fabric of folklore. It has watched the Jacobite banners rise and fall, from desperate crossings to the echoes of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s doomed rebellion in the 18th century. It has felt the weight of history in Wallace and Bruce’s campaigns for a free Scotland and the hurried strokes of government troops launching the Loch Lomond Expedition to cut off the southerly advance of the Highland Jacobites. A lake of shifting mists and shifting allegiances, it remains a witness to the slow march of time, reshaping both land and people.

Beyond its battles and exiles, Loch Lomond has long stirred the imagination. It has been a muse to poets, painters, and wanderers alike; its deep, glacial waters and scattered islands inspiring the verses of renowned poets like Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth, who found in its quiet vastness the echoes of something timeless.

As an ecologist, I see another layer to the loch’s significance, one grounded not just in the echoes of history, but in the rhythms of nature. Its true worth is written in the rippling waters, the hidden currents, and the life that stirs beneath the surface – a value not merely sentimental, but ecological. This understanding is embodied in the University of Glasgow’s field station, the Scottish Centre for Ecology and the Natural Environment (SCENE). First established to explore the loch’s natural riches, it has since grown into a cutting-edge research hub addressing questions that extend beyond Loch Lomond itself, across Scotland’s freshwater systems into broader ecological themes.

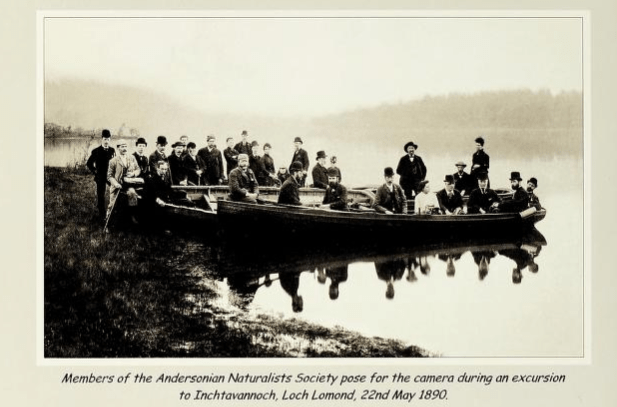

Yet SCENE is not merely a modern institution. It stands on the shoulders of pioneers, echoing the work of early intellectuals like the Andersonian Naturalists who, in the 19th century, took to these shores with magnifying glasses and boundless wonder. Their meticulous observations – cataloging fish, birds, and the shifting moods of the loch – were among the earliest systematic studies of the region’s biodiversity. In many ways, their spirit of exploration still lingers in the wind that ripples across the loch’s surface.

The origins of SCENE can be traced back to 1946 (although its name wasn’t SCENE for decades to come), when Harry Slack, a pioneering fisheries scientist, established the first freshwater field station at Rossdhu House on the western shore of Loch Lomond. Utilising old army huts, Slack set up the station to study the region’s aquatic ecosystems, with a particular focus on its fish populations. His work on the powan (Coregonus clupeoides), a glacial relic species found in only a handful of Scottish lochs including Loch Lomond and one of Scotland’s rarest fish, provided the first detailed insights into its life cycle, habitat preferences, and conservation needs.

Come 1964, the University Field Station (its name in those days) moved to its current location near Rowardennan. Building on Slack’s foundation, Peter Maitland, one of Britain’s foremost freshwater ecologists and a PhD student of Slack, deepened our understanding of Loch Lomond’s diverse fish communities. His research explored the interactions between native species like Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) and powan and the ecological pressures introduced by non-native species such as pike (Esox lucius) and perch (Perca fluviatilis). Maitland was a key researcher at the station in the 1960s and his meticulous surveys and long-term monitoring efforts not only helped shape conservation strategies but also highlighted the impacts of climate change and human activity on the loch’s delicate ecological balance.

While Slack and Maitland focused on species interactions, Roger Tippett, who took over from Slack as the Director from 1972 to 1995, turned his attention to the broader limnological and environmental processes shaping Loch Lomond. His work on water quality, nutrient cycling, and the physical dynamics of the loch provided crucial insights into how these factors influence aquatic life. Tippett’s research established a key baseline for monitoring ecological change, ensuring that shifts in the loch’s health could be tracked over time.

In 1995, Tippett handed over the reins to Professor Colin Adams, whose long-standing association with SCENE has ushered in a new era of ecological research. Adams, a passionate freshwater ecologist and conservationist, has expanded SCENE’s focus to encompass riverine and upland freshwater systems across Scotland. His leadership has seen the integration of molecular tools, telemetry, and landscape-level approaches to freshwater ecology, helping bridge the gap between field biology and conservation policy. Under his direction, SCENE has not only deepened its work on iconic species like Atlantic salmon and lamprey, but also played a pivotal role in shaping Scotland’s freshwater biodiversity frameworks. More than a scientist, Adams is a mentor and visionary who sees the loch not just as a research site, but as a place of learning, curiosity, and belonging – a philosophy that will hopefully continue to shape the ethos of SCENE in the future.

Fast forward to 2024, and a new chapter began under Professor Chris Harrod, who has taken over as Director of SCENE, ushering in yet another exciting chapter for the field station. An internationally recognised expert in stable isotope ecology, Chris brings a dynamic energy and a wealth of experience in food web ecology and fish biology. With a keen eye for ecological interactions and a commitment to innovation, he has already launched several promising research initiatives that build on SCENE’s legacy while expanding its scientific horizons. His deep enthusiasm for fish, and for ecological storytelling more broadly, is infectious, and it’s clear that his leadership will continue to shape SCENE as a place of scientific curiosity and collaboration. I’ve had the pleasure of working with Chris since last September on a project mapping the food web of a small, enigmatic dystrophic lochan near the station.

Together, these scientists have laid the groundwork for the establishment of SCENE, which evolved from its humble beginnings at Rossdhu House into a world-class research facility on the loch’s eastern shore. Their legacy endures in the work carried out today, where state-of-the-art techniques and long-term ecological monitoring continue to unravel the mysteries of Loch Lomond’s ecosystems.

As the decades rolled on, SCENE grew from a small, local field station into a global hub for freshwater ecology. By the late 20th century, its researchers were probing deeper into questions of climate change, invasive species, and the fragile balance of aquatic ecosystems. In 2007, the current facility was established and received its current name of the Scottish Centre for Ecology and the Natural Environment. Seven years later, in 2014, a major transformation gave the centre a new lease of life – modern laboratories, teaching spaces, and accommodation now stand where previous generations of scientists once huddled in simpler quarters, their research fueled by rain-soaked notebooks and the occasional dram of whisky.

SCENE remains at the frontier of freshwater science, tackling questions that stretch far beyond Loch Lomond’s shores. How do lakes respond to a warming world? What unseen currents shape the lives of fish and invertebrates? And, perhaps most intriguingly, how does this ancient, glacially-carved body of water fit into the vast and intricate story of our planet’s ecosystems?

Though the tools have changed (from magnifying glasses to molecular kits) the essence remains unchanged. SCENE is still a place where landscapes whisper their secrets, and each ripple on the loch’s surface tells a story, waiting for the next generation of researchers to listen.

Written by MRes student Kanishk Walavalkar. Edited by Lucy Gilbert & Taya Forde. Photos courtesy of SCENE collections.