Over the course of my veterinary research career, I have had the privilege of visiting and working in many beautiful and fascinating places. Much of this has been in tropical locations, such as Guatemala, the Philippines, Tanzania and Thailand. Compared with my native Canada and my adopted home of Scotland, these countries represent a taste of the exotic – from colourful landscapes, to a huge diversity of flora and fauna, to unique cultures. The French word ‘dépaysement’ captures this feeling well: the sense of being far from one’s country or normal day-to-day. However, some of the greatest sense of adventure and remoteness I’ve experienced has actually come from travel within my home country.

From 2022-25, I was incredibly fortunate to receive funding from the Canada-Inuit Nunangat-United Kingdom (CINUK) Arctic Research programme. This was a novel funding scheme supported by both the Canadian and UK governments, covering a diverse range of projects that were co-led by Canadian and UK researchers alongside Inuit communities, which addressed priorities identified by these communities. This was an amazing funding model that truly promoted research co-development among academics and Inuit organisations.

Our ‘ArcticEID’ project sought to improve our understanding of the emergence of bacterial diseases in Arctic wildlife. Among these is a bacterium call Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, which our team sometimes referred to affectionately as ‘the E-word’. This is a bacterium that – since 2010 – has been causing widespread and large-scale mortalities in muskox populations. These iconic northern herbivores represent an important food and cultural resource for the Inuit, and therefore a better understanding of these recent outbreaks was important not only for wildlife conservation but also for food security.

Just as our project proposal was being submitted in the summer of 2021, my collaborators at the University of Calgary were informed of unexplained mortalities in muskoxen on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian high arctic. My colleague Prof Susan Kutz managed to get up to the location within a few days to conduct an outbreak investigation, and – sure enough – the E-word turned out to be the culprit. This began a multi-year outbreak investigation, led by researchers from the University of Calgary and scientists from the Government of Nunavut, Canada’s largest and most northern territory. I was lucky enough to join in the field investigation in its second year, in August 2022. The following is a brief account of my experience traveling to this remote part of Canada.

Planning

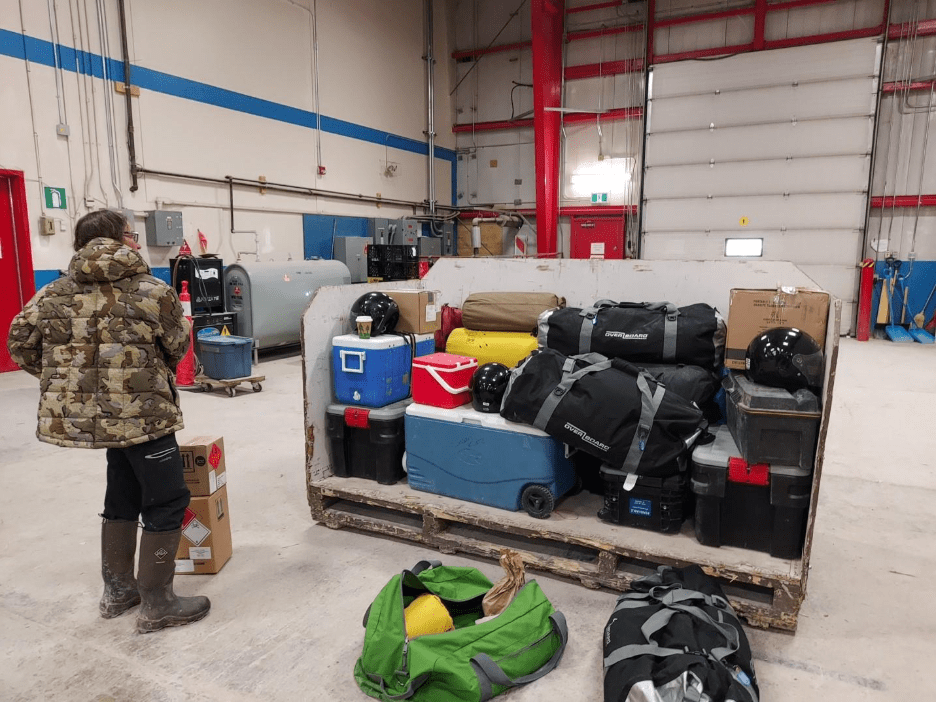

Given the remoteness of our field site, a lot of work went into making sure we had all the equipment and supplies we would need for a little over one week in the field. Thankfully, the Polar Continental Shelf Program – a research centre of the Government of Canada that supports Arctic field work, based in the small community of Resolute Bay, Cornwallis Island, Nunavut – was able to provide a lot of this for us. We needed to develop our list from their extensive catalogue, and then spend a couple of days in their seriously impressive warehouse getting our things together. I was mostly in charge of the food, much of which we brought with us from ‘down south’, since groceries in Resolute are somewhat limited (and expensive!)

My colleague Prof Susan Kutz, from the University of Calgary, Canada, surveying our field equipment in the PCSP warehouse. Our supplies didn’t stay this clean for very long… Photo: T. Forde

Getting there

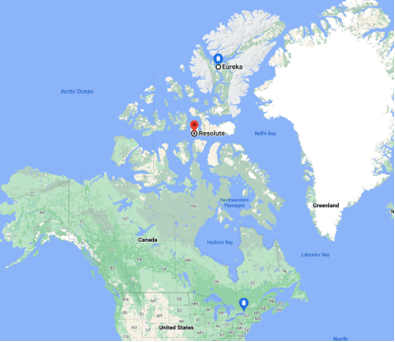

Lower pin: Ottawa, Ontario, Canada’s capital. Red pin: Resolute Bay, where PCSP is located. Upper pin: Eureka on Ellesmere Island’s Fosheim Peninsula.

Resolute Bay, at 74 degrees North, well within the Arctic Circle is already much farther north than most Canadians ever travel. From there, we had another ~2.5-hour flight north in a fixed-wing aircraft to Eureka – a tiny weather station and military airstrip on Ellesmere Island, Canada’s most northerly island. Making this flight is far from guaranteed – due to frequent high winds and other challenging weather conditions, researchers have been known to be stranded in Resolute waiting to head to the field for up to several weeks! Fortunately, we were blessed with good weather both in and out.

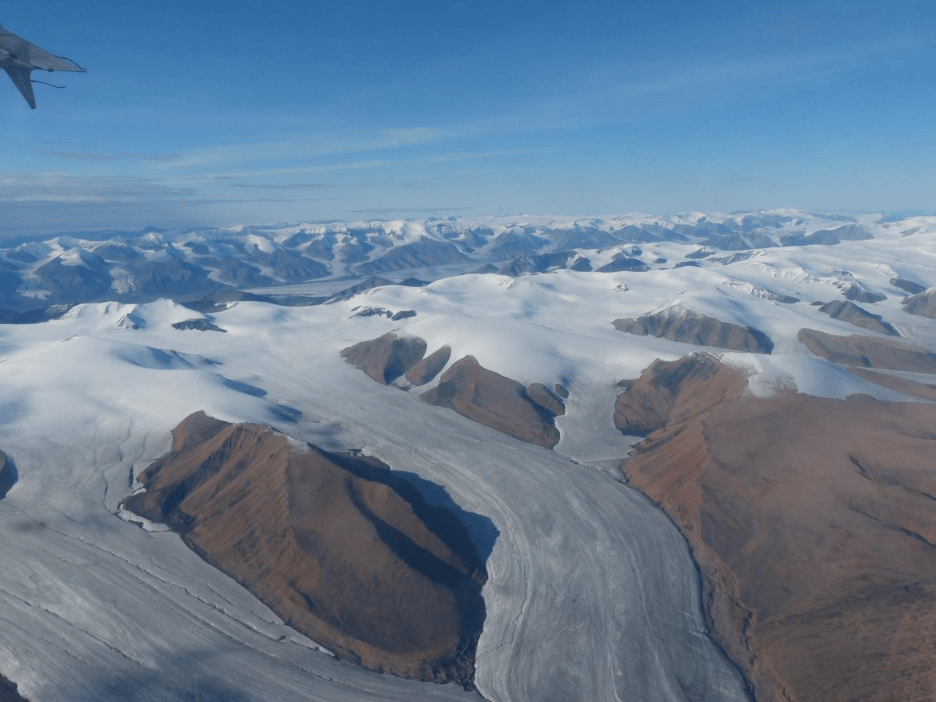

The view over Axel Heiberg Island (to the west of Ellesmere) and its extensive glaciers was stunning. Photo: T. Forde

But our journey didn’t end in Eureka. There, we unloaded all our gear from the plane and packed up our trailers and quad bikes before heading out on our ~30 km travel overland to our campsite.

Loading quad bikes and trailers on the Eureka air strip in preparation for heading to our field campsite on the Fosheim peninsula of Ellesmere Island. Photo: T. Forde

Quad biking

Sometimes we end up doing some surprising things as part of our research. Before this trip, I had zero quad biking experience. That is, with the exception of one day of off-road quad bike training that I managed to take in Perthshire, Scotland. Thank goodness I did this! After landing in Eureka, we were on our bikes for multiple hours every day, crossing rivers, climbing hills, traversing rutted ground, and occasionally getting stuck in mud.

The author on some of the better bike tracks on Ellesmere Island, laid by previous film crews. Photo: S. Kutz

Meet the Team

After being dropped off at Eureka, there were just three of us alone in the field. I was fortunate to be out there with two highly experienced women: my colleague Susan Kutz, and wildlife biologist Tabitha Mullin, from the Government of Nunavut. Tabitha is – among other things – responsible for polar bear management around Resolute, so I felt I was in very good company!

Tabitha Mullin, Taya Forde and Susan Kutz during field work on Ellesmere Island, 2022.

Tabitha Mullin taking a break on one of our quad bikes after sample collection. Photo: T. Forde

Home sweet home

The week on Fosheim peninsula was spent in individual tents, pitched alongside a very large dome tent that was used for sample preparation in one corner, and food preparation in another. It worked very well, except for one day of very high winds, where we returned from the day out to find the tent folded in on itself. Thankfully, it stayed pegged in, and we didn’t find it blowing across the tundra!

I was very grateful that I had a buff with me that I could use to cover my eyes at night. At that latitude in the summer months, it never really gets dark.

Setting up camp on the Fosheim peninsula of Ellesmere Island, August, 2022. Photo: T. Forde

Our campsite once assembled. Photo: T. Forde

Field sampling and observations

During our week in the field, we aimed to return to all the mapped (GPS-marked) locations of muskoxen that had been found dead in the previous year, as well as to look out for any new or previously-undocumented carcasses (of which we found several). We collected samples from all sites we identified, including bones (since the bacteria seem to survive well in bone marrow), soil from below the carcass, and any insects or scavenger faeces found nearby.

Susan Kutz and Taya Forde disarticulating a long bone for collection, with eventual bacterial isolation from the bone marrow. Photo: T. Mullin.

Despite muskoxen being large animals, it was surprisingly difficult to find carcasses, even when we knew their previous location. This is not only because of scavenging and decomposition, but also because of the undulating landscape features, making it difficult to see into small depressions. This really made me appreciate how fortunate we were to have been informed about these cases in the first place – even in a location with a lot of human traffic, these mortalities could easily have been missed.

Our results over the multi-year follow-up show that the bacteria can persist at these carcass sites for several years; a manuscript is currently in preparation.

Muskox carcass on the tundra, approximately 1 year old. Photo: T. Forde

Sadly, over the week we were traveling around the Fosheim peninsula, we saw more dead muskoxen than live ones, hinting at the impact of the mortalities on this population. We didn’t see any calves that summer, but I am happy to report that calf numbers increased over subsequent summers. For those muskoxen we did observe, it felt like such a privilege seeing these animals up close in their natural environment.

A group of muskoxen on the north shore of the Fosheim peninsula, Ellesmere Island. Photo: T. Forde

Female and male adult muskoxen seen up close. Photo: T. Forde

We noticed that some of the live muskoxen had strange lesions around their eyes, and we were able to capture some of these in photos. We later worked with the film crew that had been there the previous summer to review video footage they had collected, and found this was quite a widespread issue in 2021 as well. The cause is still a source of conjecture.

Adult male muskox with lesions of crusting and hair loss around the eye. The cause remains unknown. Photo: T. Forde

Overall impressions

The week that I spent in the field on Ellesmere Island was full of challenges and surprises, but perhaps one of the things that I found most remarkable was the beauty of the landscape. While this part of the world falls well north of the tree line and spends much of the year covered in ice and snow, when summer arrives it brings with it a diversity of plant life, including a variety of wild flowers.

I feel incredibly privileged to have experienced this part of the world that very few people have the good fortune to visit.

Purple saxifrage next to a small riverbed. Photo: T. Forde

The Author. Photo: S. Kutz

Bio: Dr Taya Forde is a senior lecturer in the School of Biodiversity, One Health & Veterinary Medicine. She studies a range of bacterial infectious diseases.

Want to hear more?

-Manuscript describing the multi-year outbreak investigation (Scientific Reports): https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-27316-y

-BBC Earth covering the muskox mortalities on Ellesmere Island – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zpjSma6WFbs